Player choice is a constantly evolving concept in the games industry. If you really get down to it, the player has always been able to make choices, from steering through mazes in Pac-Man to deciding if you want to ditch the Tanooki Suit for a Fire Flower in Super Mario Bros. 3. But as games have evolved, the mechanics that drive meaningful decisions have only grown more complex.

In the late-1990s and into the aughts, a lot of game developers were toying with the idea of moral choices having an impact on gameplay. Notable examples include Star Wars Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II (1997) and Fable (2004), and later games like BioShock (2007) and Dishonored (2012) would expand upon these moral systems in profound and interesting ways.

And then there’s the concept of dialogue trees, which you’ll see in Mass Effect (2007) and Telltale’s The Walking Dead (2012). I think dialogue trees have become pretty standard at this point, though games don’t always make those as meaningful as they are in the games I mentioned in the previous sentence.

So I’m pointing out five games that use choice in interesting ways. Because of the agency they give players, all of these are good examples of how games can interact with the player, and where games can go as a truly interactive medium.

Honestly, this list might as well be called “Five Games That Lucas Really Likes,” because I could write a whole article on each of them, and I love games that make their choices feel meaningful. All of these games are more than that, though, so I want to cover each one in a good amount of depth.

Just so you know ahead of time, there will be heavy spoilers for every single one of these games. It’s sort of hard to talk about these interactive experiences — and to specifically talk about the importance of choice — without spoilers. There will be an image after the title of each of the five games, giving you some space between the title and the content, so if you don’t want to have one of these games spoiled, you should have time to back away before things get too intense.

Also, there is some potentially disturbing content here, so be warned. One game on this list is about war, violence, PTSD, and psychosis, so there’s a lot there. Other entries on the list include murder, psychosis, breaks from reality, and toxic relationships with a lot of insulting or combative dialogue. If these things upset you, I won’t feel bad if you turn away now. In fact, if you’re looking for something more lighthearted and chill, you can instead check out this list of cozy, relaxing games on Steam.

With all that said, let’s talk about five games that use choice in unique and interesting ways.

Night in the Woods

I think of all the games on this list, Night in the Woods is the most unique in how it presents choices to you. Instead of giving you big set-piece moments where you are presented with major decisions, Night in the Woods presents its choices subtly. You may not realize your decisions are important until the end of the game — and in some cases you, might not even realize at all. The game presents small decisions each day, which taken together may alter the course of the game.

The main decision you would probably be aware of is whether to spend time with Gregg or Bea. Each of these characters has a storyline associated with the time you spend with them, and your friendship with either of them will evolve as well.

However, a lot of the game is spent wandering around the protagonist Mae’s hometown after dropping out of college, and a lot of the choices that affect the game come into play through small interactions every day with anyone you talk to. The more you talk to each person around town, the more they will open up to you, which leads to extra bits of story you can only earn through these “unlockable” moments.

My friend Dan introduced me to the game, and we talked about it pretty extensively after I finished. He had played it a few times, so he knew a lot about it at that point, and I was surprised to learn just how much this game can change based on the choices you make.

“I never found out what was behind the crawlspace,” I told him.

“That one is pretty specific,” Dan said. He explained that you need to watch TV with Mae’s dad every time he asks, and he’ll clear it up.

Then there’s a safe that you need the combination to from examining the bookshelf every time you can. Even if you find the combination, there’s a tooth in the safe. You would only know if you were paying attention to old news articles that that tooth is from a worker’s resistance where they removed a mine boss’s teeth for underpaying them. You can give it to Mae’s dad at the end, who seems touched and surprised by it.

“I did infest the town with rats,” I told Dan.

“Did you go to the abandoned supermarket after?” Dan asked.

“No. What happens?”

“Oh, there’s a whole montage where Mae sees the rats all over the store.”

The game is full of moments like these: moments that are easy to miss but will reward inquisitive players. The game encourages multiple playthroughs so you can uncover all of its secrets.

I think this style of choice-based narrative works well with this game’s themes and aesthetics. Decisions are cumulative in that the initial interactions are casual and light, but when taken together, they combine to create something bigger. This game is very true to life in that you may not always recognize the value of interactions with other people — or even the value of specific moments — until you look at them in retrospect.

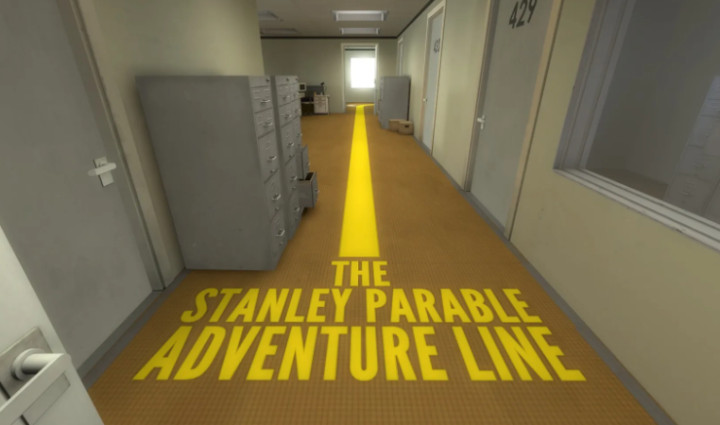

The Stanley Parable

The Stanley Parable is all about choice, in that the choices you make are the entirety of the game. The only options you have as a player are to walk around and occasionally press buttons, yet this game is still entirely engaging.

There are two main characters here: you and the narrator. But in a way, there are three characters, because Stanley is you, but he’s also separate from you in some ways. And the narrator is supposedly congruous with the story, but you’re allowed to obey the narrator or completely disregard their words and do your own thing. The game draws you in by exploring the tension between the narrative and meta-narrative.

The premise is that the narrator is trying to tell a story, acted out through Stanley, who is controlled by you. But players are given a great deal of agency to change the story. Do you just do what your told, or do you do the opposite? And even if you choose to do the opposite, isn’t the narrator still kind of in control, in some ways? If there are the options to go left or go right, and the narrator tells you to go left, aren’t you only going right because the narrator said not to? If so, how much choice did you really have in the matter?

If you obey the narrator completely, you’ll see an ending in which Stanley is “free” and “in complete control.” But then there are all sorts of alternate endings based on how you disobey in different scenarios. At your most rebellious, you’re taken completely outside the game’s world and end up in Minecraft and Portal, as well as an empty room with untextured walls. You are criticized by the narrator for being a contrarian, and ultimately left to wander (in the original map of the game from a Half-Life 2 mod) to create your own story.

When every path you can walk has been created for you long in advance, death becomes meaningless, making life the same.

Narrator, The Stanley Parable

The endings I mentioned so far are on the extremes of complete obedience and complete disobedience, but there are several different endings that fall somewhere between these extremes. You may turn out to be in the room the whole time and daydreaming the game as an escape. You may be disconnected from Stanley and watch him never decide where to go. You may find an ending where you repeatedly jump off a scaffolding to escape the narrator’s Zen paradise. My favorite ending is the confusion ending, where you’re trying to “find” the story and are utterly lost.

The game world’s layout will actually change depending on which way you go. This becomes apparent with nonsensical pathways and rooms that cycle endlessly no matter which way you go. Each ending is a sort of meta-joke, a commentary on your choices as the player and your relationship with the game’s designer.

Loved

I had considered including this one in my list of my favorite Flash games, but I limited myself to just five games for that list, and this current list is a better place for Loved anyway.

Loved is a very simple Flash platformer with the only characters being you and the “narrator” of sorts. I would recommend playing this one on Flashpoint, though if you can find it online, that works too. Just do not download Kongregate’s SuperNova player, because it seems to be having problems with malware.

Like The Stanley Parable, Loved explores the relationship between a narrator and the player. The difference is that Loved explores these concepts in a very minimalistic and abstract way rather than an absurdist one.

The narrator only appears to ask you a question or give you directions. The game starts out with the question “Are you a man or a woman?” If you choose man, the narrator will then respond with “No. You are a girl.” From there, the narrator will continue to call you the opposite gender you chose. A lot of the questions take on this sort of contradictory and dominant role, perpetually putting you in an uncomfortable state.

When the narrator gives you a direction, you are able to obey or not, and the world reacts to how you respond to the narrator. If you don’t obey, the world becomes more obscured. Colors appear, but in a way that’s mostly distracting. In contrast, when you obey the narrator, the world becomes clearer.

The ending changes based on your choices, showing that the way you interacted with the narrator throughout the game also impacts how they feel about you. “I am so happy that you are mine” or “Why do you hate me? I loved you.” Choices are very binaural, but their execution is compelling, questioning what you’re willing to put up with and what it means to follow orders. Rather than simply choosing X or Y, you have to actively do something you might not like, such as redo a whole difficult section of the game in order to appease the narrator.

The game is ultimately vague and abstract, so there’s a lot of room for interpretation, but I think it offers commentary on the effects of toxic relationships with manipulative people, and how easily our perception can be shaped by others.

Spec Ops: The Line

I recently did a retrospective piece on Spec Ops: The Line, in which I called it “a military shooter on the surface, but it’s actually a psychological horror game dressed up in shooter clothing.”

And it’s true. Spec Ops: The Line seems like a pretty generic, Call of Duty-style first-person shooter on the surface. But eventually, it unfolds into a psychological drama about PTSD and the morality of war. It presents with what seem like binary choices (do I rescue a farmer accused of stealing, or the soldier who killed the farmer’s family?) and then allows you to color outside the lines (what if I try to save them both?)

Ultimately, though, Spec Ops: The Line is constantly goading you into making immoral choices so it can underscore the idea that corruption is subtle and pernicious, and almost never black and white. And the most impactful choice it asks you to make — without saying it outright — is the choice to keep playing and committing atrocities, or to just shut it off and enjoy your day doing something more positive.

I could talk about Spec Ops: The Line all day, but I won’t do that now. If you want a much deeper dive into the way this game uses choice, check out my retrospective piece on it.

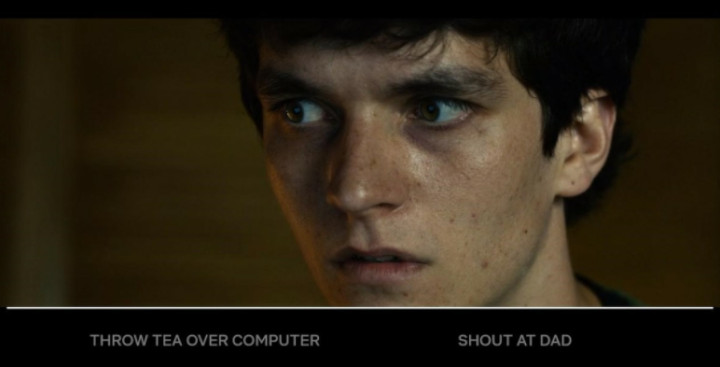

Black Mirror: Bandersnatch

Is Bandersnatch even a video game? It’s debatable. It’s a Netflix film, sort of. But it’s also interactive in a way that’s unusual for a movie.

The story follows a character who is creating a video game based off of a choose-your-own-adventure book he liked. And the “gameplay” itself is a choose-your-own-adventure. We can probably agree that a choose-your-own-adventure book isn’t a video game, but how about a choose-your-own-adventure movie? That’s sort of debatable. The way choice works here is actually not far off from a Telltale game or Life Is Strange. At key moments, you make a decision, and then the narrative moves forward based on what you choose.

This project is the most meta take on the choose-your-own-adventure narrative I’ve ever seen. On top of the fact that the story is about a game designer named Stefan, who’s making a choose-your-own-adventure game, we are allowed to make choices for him.

These choices are arbitrary at first, but their impact grows as the story progresses. The twist here is that the narrator is on some level aware of… us. He knows that someone is stepping in and making these choices for him, and he tries to resist them at times. There is one storyline where you can do acid with The Colin Ritman, a role model and video game designer extraordinaire. All of a sudden, Colin just starts ranting about diverging realities in a monologue that’s surprisingly apt for how the universe works within this special.

People think [Pac-Man] is a happy game. It’s not a happy game, it’s a [expletive] nightmare world. And the worst thing is, it’s real and we live in it.

Colin Ritman, Bandersnatch

The pacing of this episode is outstanding. The apparent “goal” of the game is to get 5 stars (out of 5) for Stefen’s game, but you are also allowed and encouraged to explore different consequences for different choices you make. By the end of the experience, the stakes have gone up to an absurd degree. You may end up in a universe where everything is fake and Stefen is part of a mind-control experiment. You may kill your dad and make the perfect game. You may reveal that it actually is all a Netflix show, only for Stefen to be still convinced he is Stefen and not an actor. Each ending recontextualizes the script, and each one could be just as real as any of the others.

There really isn’t any way to “win” Bandersnatch; you can only determine the reality that works best for you.

Conclusion

I highly recommend all five of the games on this list. That being said, not all of them are fun, exactly. Spec Ops: The Line can be downright grueling. Bandersnatch is twisted in the way that Black Mirror typically is.

Despite that, each of these games has something to say, and each one uses choice as a way to bring you into the conversation. They want you to be involved. After all, a game is nothing without the player. And really, the reason all of these games work is that they know how to respect their players.

The five games on this list aren’t just good examples of how choice works within video games, they’re also cutting-edge experiences that explore what choice means within an interactive framework. And what medium is better suited for exploring this concept than video games?