Despite the drip-fed content leading up to the release of Ghostwire: Tokyo, it’s fair to say that I stayed on the fence until the game’s launch was almost upon us. I liked the general art style and the crazy finger-weaving animations, and the vibrant-yet-spooky appeal of a desolate open-world Tokyo felt fresh and exciting to explore. But there was an alarming lack of clarity when it came to what one might expect from the moment-to-moment gameplay elements. It felt like, to commandeer a familiar Seinfeld trope, “What is the deal with this game?”

But once I started to see less edited snippets of gameplay via previews and impressions (in the week leading up to the game’s launch), I started to get the feeling that Ghostwire: Tokyo, whatever it was, was definitely something I could vibe with.

Now that I’ve spent about 30 or so hours playing through the story and completing a good amount of the side content, I can safely say that Ghostwire: Tokyo is an enjoyable experience, but also one rooted in game design choices from a decade or more ago.

Ghostwire: Tokyo’s approach to open-world design follows a bit of the old Far Cry template. As protagonist Akito (who is possessed by the spirit of the spirit hunter KK), players will spend a good deal of time bouncing from Torii gate (i.e. enemy camp) to Torii gate in order to clear up the map’s fog. Not only does this allow for safe travel in areas otherwise clouded by the harmful fog, but it also populates the map with side quests, power-ups, and other markers. At the end of the game, my map was littered with these icons, some of which were atop others (on PS5, you can use the triangle button to cycle between them).

The story is rather straightforward, at least in terms of what’s happening and what motivates the protagonist, and it doesn’t really do much to advance the art of video game narratives.

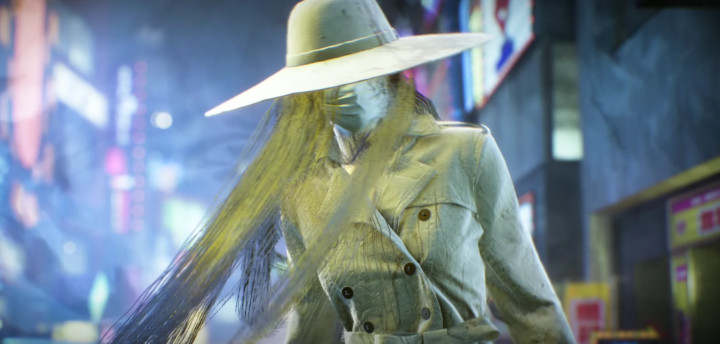

Ghostwire: Tokyo starts from the perspective of KK, who’s floating around, desperately looking for a body to inhabit as a mysterious fog engulfs Tokyo. Anyone caught in this fog vanishes, leaving behind a pile of clothes and belongings. KK stumbles upon Akito, who just crashed his motorcycle on they way to the hospital, where he planned on visiting his ailing sister Mari.

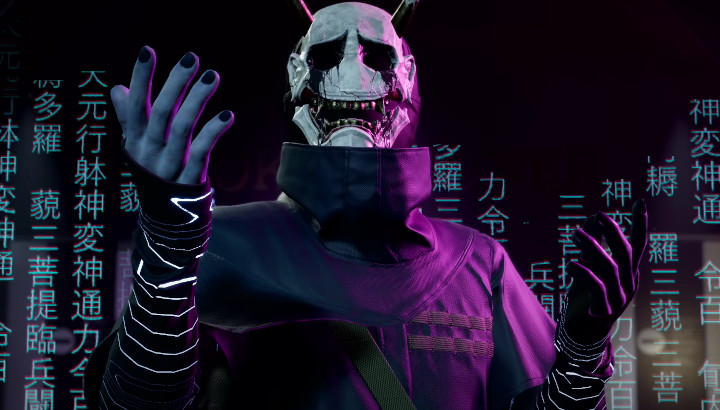

Once inhabited by KK, Akito manifests the ability to use KK’s finger-weaving elemental powers (i.e. finger guns) to fight back the invading horde of Visitors. These Visitors come in all manner of spooky Japanese Yokai, from slendermen with umbrellas (when the umbrellas are lowered, they will block two of your three elemental attacks) to headless schoolgirls to creeps that literally look like the crappy tissue ghosts we used to make for cheap Halloween decorations.

Akito’s quest to save his sister is pretty eye-rolling, especially in the wake of Dying Light 2: Stay Human earlier this year (which started with the same flimsy motivation for its main character). But KK’s story is a bit more interesting, and it serves as the main focus of the game’s narrative. KK is trying to stop an illusory madman hellbent on uniting the realm of the dead with the world of the living for pretty vague yet still incredibly nefarious reasons. The fact that Akito’s sister is the perfect vessel for the bad guy’s plan (for whatever reason) ties the two character’s narratives together.

The setup is wrapped up pretty quickly. This is a blessing, because Ghostwire: Tokyo is at its best when you are simply left to engage with its admittedly-thin-yet-still-visually-impressive combat, while dispatching a shallow variety of enemy types. In total, there are maybe a dozen or so varieties of Visitor, with the bulk of them introduced in the opening chapter and only a smattering doled out throughout the course of the rest of the game.

This is a bit of a letdown, as you’ve probably seen a majority of them in trailers for Ghostwire: Tokyo. At the same time, each one has a very specific combat style that, when combined with other enemies, can lead to a good deal of juggling on the player’s part. There’s a nice amount of challenge without too many frustrating or cheap fights.

When I was able to simply meander around this version of Tokyo — always at night, always wet, sometimes actually raining — I enjoyed the game the most. The recreation of Tokyo is engaging and mesmerizing, by far the best element of the overall package. It harkens back to the level of detail and immersion of games like Yakuza, albeit stripped of the hustle and bustle of the denizens of Kamurocho. There are no NPCs in Ghostwire outside of cats, dogs, floating cat shopkeepers, and specific spirits scattered about, which serve as the main source of side quests.

The true testament to the strength of Ghostwire: Tokyo, though, is how long I was able to play it without getting bored. It wasn’t until the final two chapters when I started to notice fatigue setting in, even though I was engaging with all of the side content. If developer Tango Gameworks had pushed things just a bit further, I probably would’ve had a much sourer taste in my mouth in the game’s final stretch. But there’s a restraint here that I actually admire (especially after the recent barrage of open-world game launches).

Unfortunately, the final chapter sort of devolves into a walking simulator, diving deep into the emotional aspects of the characters. It’s not handled well, and it feels out of place here — this very much had me running for the exit, as it went on for what felt like a near eternity.

Before this final chapter, the game hardly dealt with the bond between Akito and Mari, occasionally peppering in a few moments of introspection (two or three lines of dialogue here and there). So this emotional crescendo felt like an unearned examination of Akito’s psyche and his connection to his family. My eyes could not stop rolling. Thankfully, there are a couple clever-yet-manageable boss fights that liven things up a bit and help make the soap-opera-level narrative go down a bit easier.

Despite its flaws, I really enjoyed Ghostwire: Tokyo. It’s a rare, almost-indie gem with a triple-A budget, which you just don’t see much of these days. In fact, the last game I would file in that category is Death Stranding. It is perhaps telling that Death Stranding was also the product of a Japanese developer who was given the budget to realize his unique vision. When compared to the current crop of Western-developed open-world games, Japanese developers definitely stand in stark contrast. From my own (admittedly Western) perspective, I think these types of games make up for any gameplay shortcomings with ideas and concepts that may seem odd or whacky to our sentiments, but don’t just blend in with the pack.

But it’s also kind of hard to recommend Ghostwire: Tokyo. I think it takes a very unique palate to appreciate its better parts while overlooking its jank and repetitive nature. I want games like Ghostwire to succeed so there continues to be a market for more games like it. If you think this game is even a little up your alley, you should give it a shot, but it might be best to wait for a sale if you are on the fence. It’s hard to justify a full-price gamble when the scales could end up tipping slightly to the wrong side.

Ghostwire: Tokyo is a glass half full of an unassuming pale lager; it might not overwhelm you out the gate, but it’s full of good spirits and it gets the job done.